Chinese Painted Clay Sculptures

Clay sculpture – not to be confused with Stucco – is a style of carving unique to China, particularly to the caves dwellings and temples in Shanxi province (Sangxi) in the north.

A Painted Clay Ming Dynasty Sculpture of Guanyin, c. 1368-1644, 109 x 85 x 52cm

Clay sculpture – not to be confused with Stucco – is a style of carving unique to China, particularly to the caves dwellings and temples in Shanxi province (Sangxi) in the north.

The style was first adopted in the Northern Wei (534-550 AD) and Northern Qi (550-577 AD) Dynasties and its popularity carried over into the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) Dynasties. It reached its peak during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and flowed onwards into the Yuan, Ming & Qing Dynasties.

The sculptures offered here are from the Ming Dynasty, but due to the nature of them being temple sculptures they have been conserved over the centuries.

Pictured: Our main work, the monumental Guanyin (lot 55) dates to the Song Dynasty 960-1279. Bid or see more on Invaluable.

The unique characteristic of this sculpture is that it is made in situ and rarely moved from its original location. Shanxi province contains intriguing underground buildings, similar to those in Coober Pedy in New South Wales. These dwellings were dug into the cliffs or accessible underground areas, containing living quarters and temples, where precious family treasures were safely held from the outside world.

During the Cultural Revolution in China, most temples doors were walled-over, leaving only a small peep-hole so that families could view the temple protected within. It is due to this protection that many clay sculptures are found in the temples from this region.

Working in situ with clay allows fine detail of facial features and postures to be sculpted, giving the sculptures soft, like-life qualities that can be more difficult to achieve in hard materials. In painted clay, the combination of the individual artistry of the sculpture and artistry of the paint-work over the work, gives this art form its unique features.

Unlike traditional clays, these sculptures do not have the protective coat offered by a glaze, nor the hardness that results from firing and so they are artworks for use and display indoors. As such, they were treasured objects, kept in protected conditions in people’s homes, temples or tombs and have lasted many hundreds of years.

The skill of the Chinese sculptors is revealed in the temple sculptures of Donghuang and Jin Temples (both from the Song Dynasty) and the Chongqing, Farxing and Shuangling Temples. These temples display large and small painted clay art, displaying a combination of realistic and mythical carvings.

Sculpting procedure

Clay sculpting is a layered process. It begins with a wooden framework, which is essentially the skeleton of the work. To this is added three layers of a clay, each containing various additional materials:

Clay layer 1 contains straw and mud mixed with 40-50% sand, the sand helping to reduce shrinkage.

Clay layer 2 contains hemp, or jute, and the same proportion of sand.

Clay layer 3, the final, is clay mixed with raw cotton, again combined with the sand.

Then the sculpture is left to dry. Any cracks are repaired with the layer three mix of clay to ensure a consistent patina. This process continues until the sculpture is totally dry and perfect. Once dry, a very fine cotton paper layer is applied with glue to the whole surface.

Finally, a smooth powder of ground mother-of-pearl is brushed on to the carving to give a fine shiny shell-like finish.

To complete the sculpture, the artist applies the paint to add details such as facial features or apparel, giving the carving its life-like characteristics over the soft skin-like surface. It is this final painting step that creates the visual appeal; the beauty of each sculpture being determined by the artistry of the painter.

Thermoluminescence (TL) Testing

Thermoluminescence (TL) dating is the process used to identify the age of sediments. In the case of pottery from antiquity, we are able to use TL testing as a way to obtain the approximate age of an ancient work of art.

Thermoluminescence (TL) dating is a process used to determine the age of sediments. In the case of pottery from antiquity, the TL testing as a way to obtain the approximate age (+/- 20-25% uncertainty) of an ancient work of art.

Pottery contains quartz-rich sediments and it is these quartz crystals that are the key to dating a work of ancient pottery. As only the quartz is used in the TL dating process, these minute grains must be removed from the bulk of materials in the clay mix.

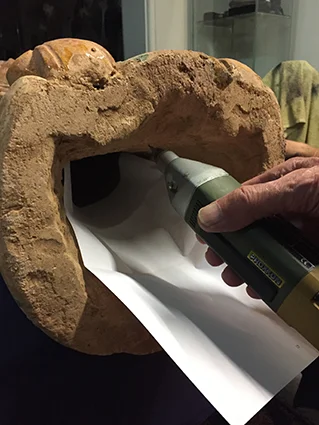

Obtaining and preparing samples

To acquire the samples, small specimens of the pottery are carefully separated using a small drill in a dark environment. These are labelled, wrapped in light-proof protective bags ready for testing.

Back in the testing lab, the samples are separated into grains that are between 1 and 8 micrometres in size. These grains are then deposited to obtain a number of smaller portions, or sample aliquotes, which are then heated to 500 degrees celsius to obtain a thermoluminescence signal.

The images below show the process of drilling to collect the powder from a pottery work of art. This is all carried out in almost complete darkness under safety lights with an orange hue.

Measuring the energy

The approximate age of the pottery is identified by examining two key measures:

The base level of TL that the pottery has absorbed (the archaeological dose) and,

The annual radiation dose received.

The older the pottery, the more radiation it has absorbed and the more the sample glows a faint blue when heated. It is this blue glow that is known as thermoluminescence and measuring its' strength (or the amplitude of the TL signal) tells us the age of the work of art.

New Book: The Social Life of Inkstones by Dorothy Ku

Social Life of Inkstones

An inkstone, a piece of polished stone no bigger than an outstretched hand, is an instrument for grinding ink, an object of art, a token of exchange between friends or sovereign states, and a surface on which texts and images are carved.

We felt it was time to bring you a review of a new book, and found this interesting publication from one of the best social history publishers, the University Of Washington Press:

The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China

An inkstone, a piece of polished stone no bigger than an outstretched hand, is an instrument for grinding ink, an object of art, a token of exchange between friends or sovereign states, and a surface on which texts and images are carved. As such, the inkstone has been entangled with elite masculinity and the values of wen (culture, literature, civility) in China, Korea, and Japan for more than a millennium. However, for such a ubiquitous object in East Asia, it is virtually unknown in the Western world.

Examining imperial workshops in the Forbidden City, the Duan quarries in Guangdong, the commercial workshops in Suzhou, and collectors’ homes in Fujian, The Social Life of Inkstones traces inkstones between court and society and shows how collaboration between craftsmen and scholars created a new social order in which the traditional hierarchy of “head over hand” no longer predominated. Dorothy Ko also highlights the craftswoman Gu Erniang, through whose work the artistry of inkstone-making achieved unprecedented refinement between the 1680s and 1730s.

The Social Life of Inkstones explores the hidden history and cultural significance of the inkstone and puts the stonecutters and artisans on center stage. DOROTHY KO is Professor of History at Barnard College. She is the author of Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding.

“A magical text. I have little doubt that The Social Life of Inkstones will become not only a point of reference, but also a book that readers simply love.”—JONATHAN HAY, author of Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China

320 pp., 105 illus., 78 in color, 3 maps, 7 x 10 in. US$45.00 HC / ISBN 9780295999180 / EB ISBN 9780295999197

Sumba's Stone Tombs

Only a short 800km off the northwest of Australia’s Kimberly coast lies the Indonesian island of Sumba. The tradition of megalithic burials is one that survives from the Neolithic and Bronze ages and it is one of the few places in the world where it continues.

Only a short 800km off the northwest of Australia’s Kimberly coast lies the island of Sumba.

A part of Indonesia’s East Nusa Tenggera province, Sumba’s geography is unlike the wild volcanic islands to its north. In places it more resembles its neighbouring island of Timor with its rugged mountains and hilltop villages.

In other areas, it contains open grasslands over rolling hills. It is in these regions were the pre-harvest fertility ritual of the Pasola takes place – a ritual spear or lance battle, with villagers fighting in violent confrontations from horseback that result in the occasional death.

Local arts are characterised by naturally-dyed and handspun ikat fabrics, carved timber spears used in the Pasola, elegant bamboo and thatched-roof houses with almost vertical spires in the centre, and most spectacularly, megalithic tombs.

The tradition of megalithic burials is one that survives from the Neolithic and Bronze ages – and through Portuguese and Dutch colonial administration – and is one of the few places in the world where it continues.

That the isolated Sumba is not really on any tourist path may be one reason that little is known about the carvings on these tombs and our knowledge about them is only recently acquired. This isolation has meant that traditional arts have remained quite intact.

The funerary rituals, of which the megaliths are a part, are still carried out today mostly for the rich villages or the nobility. Enormous stone blocks weighing anything from a few hundred kilograms up to more than twenty tons are dragged, sometimes great distances to construct the mausoleums.

There are several styles of tomb. The stones may be carved as flat table-style tombs or a flat stone top sitting on a single stone pillar or several circular or square pillars.

Some of the more elaborate tombstones (such as that pictured below) display curved arms spreading out in a geometric pattern from a central stem, often with a small ancestor figure carved in the centre of the peak. One face of these tombstones often contains another geometric relief carved into the stone.

The construction of the tombs still holds several clear social benefits:

Most obviously the tomb is a clear image of power for those who built it. Building such a structure for a clan member helps create greater credibility and standing in the community, as such it can be a useful negotiating tool by those that build the tomb when it comes to, for example, organising marriages for their sons and daughters.

The act of working together for an important common goal appears to be another benefit because building such large structures requires a clan effort, not individual effort, and the process helps strengthen relationships, stability and power structures within clans.

In the past when the Sumba society was more violent that it is today, there was an added benefit that tomb-building enhanced inter-clan relationships through combined building effort. This would have helped in resolving disputes between clans and in establishing inter-clan alliances.

References

This site shows how stones are transported and a provides a selection of other megalithic tombs.

For a detailed examination of the tombs see the PhD submission by Ronald Adams, Simon Fraser University.

The fifth greatest Chinese invention

Chinese porcelain, highly prized across Europe and the Islamic world, was one of the country’s major exports and the city of Jingdezhen (Ching-te-chen), in Jiangxi Province, has been the epicentre of porcelain producing for more than 1700 years.

“From time-to-time I have stayed in Jingdezhen to administer the spiritual necessities of my converts, and so have interested myself in the manufacture of this beautiful porcelain, which is so highly prized, and is sent to all parts of the world. Nothing but my curiosity could have ever prompted me to such researches, but it appears that a minute description of all that concerns this kind of work might, somehow, be useful in Europe.”

Chinese porcelain, highly prized across Europe and the Islamic world, was one of the country’s major exports and the city of Jingdezhen (Ching-te-chen), in Jiangxi Province, has been the epicentre of porcelain producing for more than 1700 years.

There are a number natural factors that can be attributed to the rise of Jingdezhen porcelain.

The first factor is the region's geology. Mount Gaoling, to the northeast of the city is essentially a clay mountain. Derived from the name of the mountain, the pure white clay is called kaolin, or ‘China clay’ in Europe.

The raw material from Gaoling is white powdery clay usually found mixed with other granular minerals. The purity of the clay is quite variable; in the best places, pure white clay was found, in other areas raw material from the ground was mined, crushed and rinsed to separate the prized white powdery clay from the surrounding material.

The second factor was that the town is located on the Yangtze River. This natural transport route provided an easy way to deliver the materials required for porcelain production. Clay could be brought down the smaller Donghe River to the city from Mount Gaoling, and pine logs delivered to supply the kilns. The finished porcelain products would be shipped down the Yangtze River to other parts of China, to Shanghai, and to the world.

Finally, it was the beauty and workmanship of the Jingdezhen white pottery that brought fame to the town. The porcelain products were noticed by the imperial court and desire for these beautiful works of art cemented the town’s future. More kilns were built to supply demand and then at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Imperial Porcelain Factory was established there.

Porcelain was exported around the world on an unprecedented scale with the opening of the Imperial Porcelain Factory but it was during the rule of the Wanli Emperor (1573-1620) that the kilns became the main production centre for large-scale porcelain exports to Europe.

At this time, on the other side of the world the Dutch East India Company had established strong trade links with China and in the early 1600s imported millions of pieces of porcelain. The workmanship and attention to detail of the exotic Chinese porcelain impressed the Europeans and demand quickly grew.

Following the death of the Wanli Emperor in 1620, the supply of porcelain to Europe was interrupted and local Dutch potters around the town of Delft took it upon themselves to imitate the Chinese porcelain style and designs to cater for the still strong local demand. Delft designs inspired by the Chinese originals were produced widely from approximately 1630 to the mid-1700s alongside their original European patterns of similar style.

This combination of demand and trade between Europe and the East initiated a curious circle where Delftware was not only exported around Europe but also to China and Japan. Chinese and Japanese potters, seeing the designs from Europe, then made porcelain versions of Delftware for export to Europe.

The pottery tradition is still alive in Jingdezhen, where today the town still hosts pottery markets such as the Pottery Workshop.

A brief timeline of the period

Five dynasties (907-960)

Song: Northern Song (Bei Song) 960-1126; Southern Song (Nan Song) 1127-1279

Jin (1115-1234)

Yuan (1279-1368)

Ming (1368-1644)

Hongwu (1368-98)

Jianwen (1399-1402)

Yongle (1403-25)

Xuande (1426-35)

Interregnum: Ming Mid-15th Century: Zhengtong (1436-49); Jingtai (1450-57); Tianshun (1457-64)

Chenghua (1465-87)

Hongzhi (1488-1505)

Zhengde (1506-21)

JiaJing (1522-66)

Longqing (1567-72)

Wanli (1573-1620)

Tianqi (1621-27)

Chongzhen (1628-44)

Further reading

A guide to Chinese porcelain marks

The New Yorker: The European Obsession with Porcelain

Surgeon’s Case of Instruments, 1917

As lovers of historical artefacts we are always captured by the unusual and rare, so when this beautiful surgeon’s case of instruments came to our attention through Mr Brad Manera, Curator at Sydney's Anzac Memorial, we thought it was the perfect opportunity to bring something new to you for this blog post.

As lovers of historical artefacts we are always captured by the unusual and rare, so when this beautiful surgeon’s case of instruments came to our attention through Mr Brad Manera, Curator at Sydney's Anzac Memorial, we thought it was the perfect opportunity to bring something new to you for this blog post.

This set was used in British and Commonwealth Field Ambulance and Casualty Clearing Stations during the Great War and such complete examples are rarely found today.

It is compact and robust to make it portable under service conditions and contains a wide variety of instruments that would equip a surgeon to treat a range of life-threatening battlefield injuries.

The timber case with brass mounts is constructed in the style of British campaign furniture of the 19th and early 20th century. The instruments are held in place by leaf springs in fitted trays with handles. The trays and instruments are made of stainless steel to allow them to be sterilised in a portable autoclave.

The bone saw can be seen at the centre of the top left-hand tray. Looking at this you can imagine the hellish pain the diggers had to endure out in the field hospitals all in the name of saving what lives could be saved.

An escutcheon on the lid includes the maker’s details an ‘I’ and the broad arrow War Department acceptance stamp. The ‘I’ may indicate that this set was considered suitable for service in British Imperial India, although we understand it never saw service there. Two centuries of campaigning in India had taught the British much about making durable, practical and functional military equipment.

The maker

'J. H. MONTAGUE of 69, NEW BOND STREET. LONDON', is engraved on ivory panels and set into the rim of the case. Montague was a highly regarded maker of surgical instruments from the mid-1890s. Like so many companies at the time, it sadly disappeared in the economic downturn that followed the Great War.

Egyptian Civilisation Timeline

Factsheet: A brief timeline of Egyptian civilisation

BC

c. 7000 – Settlement of Nile Valley begins

c. 5000 – Coming of farming to the Nile Valley

c. 3500 – Pre-dynastic period begins

c. 3000 – Unification of Egypt

c. 3100 – Hieroglyphic script developed

c. 2650 – Beginning of the Old Kingdom; First stone pyramid built: the Step Pyramid, at Saqqara for the pharaoh Djoser

c. 2575-2465 – The Great Pyramids of Giza built

c. 2150 – Fall of the Old Kingdom, leading to the 1st Intermediate period

2074 – Middle Kingdom begins; Egypt is united and powerful again

1759 – Fall of the Middle Kingdom, leading to 2nd Intermediate period; Occupation of northern Egypt by the Hyksos

1539 – Reunification of Egypt and the expulsion of the Hyksos begins the New Kingdom; Egypt becomes a leading power in the Middle East

1344-1328 – The pharaoh Akhenaton carries out a short-lived religious reformation

1336-1327 – Tutankhamen reigns

1279-1213 – Reign of Ramses II brings Egypt to the height of its power

c. 1150 – The New Kingdom begins its decline

728 – Egypt is conquered by Nubian kings

c. 671 – Egypt is occupied by the Assyrians

639 – Egyptians expel the Assyrians and begin a period of revival

525 – Egypt is conquered by the Persians

332 – Alexander the Great, of ancient Macedonia, conquers Egypt, founds Alexandria; Macedonian dynasty rules until 31 BC

305 – Ptolemy, one of Alexander the Great's generals, founds a Greek-speaking dynasty

196 – Rosetta Stone carved

30 – Cleopatra, the last queen of independent Egypt in ancient times, dies; Egypt is annexed by the Roman Empire

AD

33 AD – Christianity comes to Egypt

c. 350 – Last use of hieroglyphic writing

642 – Arab conquest of Egypt

969 – Cairo established as capital

1250-1517 – Mameluke (slave soldier) rule, characterised by prosperity and well-ordered civic institutions

1517 – Egypt absorbed into the Turkish Ottoman empire

1798 – Napoleon invades but is repelled by the British and the Turks in 1801

1805 – Ottoman Albanian commander Muhammad Ali establishes a dynasty; It rules until 1952, although is nominally part of the Ottoman Empire

1859-69 – Suez Canal built leading to the near-bankrupting Egypt and British takeover

1882 – British troops defeat Egyptian army and take control of the country; Hieroglyphs deciphered

1914 – Egypt formally becomes a British protectorate

1922 – Fuad I becomes King and Egypt gains independence

1922 – Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun

1953 – Egypt became independent

Note: Dates in this timeline are estimates due to the age of some of the events.

Gandhara, Aristotle and Alexander the Great

Although ruthless in battle and in the habit of annihilating the armies and rulers he defeated, Alexander did not force his culture on inhabitants of the regions he conquered. Instead he fostered longer-lasting natural bonds through dialogue and by encouraging inter-cultural marriages, which very effectively stabilised the regions socioculturally.

The Kingdom of Gandhara was a cosmopolitan culture much like the earlier Indus Valley civilisations and was located at the intersection of what is now north-west Pakistan and north east Afghanistan on the prosperous Silk Road.

The art we now prize so highly from this kingdom is defined by its fine sculptural detail, beauty and serenity. But what were the foundations of this style? To find out we have to look to Alexander the Great.

Much of the beauty of Gandharan art arises from its Greco-Buddhist blend that is a legacy of Alexander the Great who in 327 BC, at the age of 29, conquered the Achaemenid Empire – laying waste to the great armies of the Persian King Darius III who was at the time arguably the most feared ruler of the then know world. Alexander’s empire at this time was so vast it stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River.

Gandharan sculpture's appeal arises from the unusual combination of Buddhism being blended with Grecian style. That the combining of these two cultures resulted in works of such beauty may be linked to Alexander’s fundamentally Aristotelian approach to law and order of the various regions he conquered and the diverse sociocultural environments now under his control.

As a young boy of 14, Alexander’s tutor was Aristotle and they continued to correspond at various times throughout Alexander’s life. Aristotle’s approach was to introduce an idea to someone rather than force it upon them.

Although ruthless in battle and in the habit of annihilating the armies and rulers he defeated, Alexander did not force his culture on inhabitants of the regions he conquered. Instead he fostered longer-lasting natural bonds through dialogue and by encouraging inter-cultural marriages, which very effectively stabilised the regions socioculturally.

The result of the blend rather than the clash of cultures we can see in the serene Gandharan sculpture of the period such as the work depicted above. This became a unique Gandharan style and a clear departure from the region’s traditional Buddhist sculpture. In earlier depictions, the Buddha appeared through symbols only. Now he took a human form and the sculptures were more personal, often depicting episodes of the Buddha’s life and teachings.

Main image: A Gandharan Schist Frieze (c.2nd-3rd Century AD), sculpted in relief with a central Buddha within a pillared arch way (36x54cm). Sold: at one of our past auctions A$10,000

Catalogues, Memory, and Provenance

A work of art such as a painting, sculpture, or installation is a visual, tactile, and sensual product that is a physical manifestation of a human cognitive processes. Perhaps that sounds a little academic and grand, but it’s an important place to begin when talking about the benefits of publishing art catalogues.

A work of physical art – ignoring online or digital art here – transcends both the physical world in which we live and the metaphysical world: it begins as a thought and ends as a physical object.

A work of art such as a painting, sculpture, or installation is a visual, tactile, and sensual product that is a physical manifestation of a human cognitive processes. Perhaps that sounds a little academic and grand, but it’s an important place to begin when talking about the benefits of publishing art catalogues.

A work of physical art – ignoring online or digital art here – transcends both the physical world in which we live and the metaphysical world: it begins as a thought and ends as a physical object.

The world has never been more immersed in the visual as we are now. According to an internet trends report (KCPB Internet Trends), every day in 2014 there were 1.8 billion images posted online, they cannot all be classed as Art of course, but they all vie for our attention. But with all this imagery and accessibility, there is a new level of transience to these images. A Facebook post is most likely only relevant for a few hours, a tweeted image is most likely relevant only for minutes.

Art is inherently subjective and as such the way it is displayed is crucial for our appreciation of it. Poorly displayed, art loses its impact and beauty. Importantly, if art is to be shown in a publication, the reproduction needs to be executed to do justice to the work. It should be the right colour and tone, printed on good quality paper so that the texture and overall sense of the piece is retained as much as possible.

When we visit any major art exhibition, there is usually a catalogue of the event for sale. Sure, we can find any of the works on online whenever we want to, but the catalogue acts as a memento – a beautiful three-dimensional object that we can have at home, show to friends, and discuss.

Research into reading and memory now has been conducted by several psychologists and cognitive scientists. Kate Garland at the University of Leicester was one of the first. Her research shows that we retain information from reading printed reading matter better than we do digital or ebook material due to the context and landmarks that are available to us in a book. The spatial aspect – was the image on the right or left; was it at the start or in the of middle of the book – helps our brain relate to, and remember, what we see and read more quickly than on-screen. At the moment, we have evolved to operate in a three-dimensional world. In the future, we may evolve to reflect a new world of information delivery.

So printed catalogues are fundamentally visual, tactile, or sensual products. These qualities sound familiar and, of course, they are … just like the art within their pages.

In a commercial sense, catalogues are indispensable. They entice, sell, and provide a reference of provenance for art.

To sell art – or encourage people to visit an exhibition – the function of a catalogue is to record the event and entice people to come along and see the works for themselves. Sellers of art need to stimulate the imagination and senses of potential buyers to help them enjoy the whole process of looking, feeling and finally wanting a work enough, that they will buy it.

Similarly, a catalogue of a private collection, records for posterity the hunt, passion, and perhaps years of work to source the art in a collection.

In recent years the pendulum has swung towards online-only catalogues for some art auctions, but, we know through our own experience of publishing catalogues for private clients and from our auction buyers and vendors, that the printed catalogue is preferable than reading online from a smartphone or tablet in the auction room.

We love our old catalogues. We keep notes in the margins and add them to our reference library, so that one day down the track we can retire to the lounge with a coffee, tea or single malt, and peruse our memories at our leisure.

New Book: Ardor

In this revelatory volume, Roberto Calasso, whom the Paris Review has called 'a literary institution', explores the ancient texts known as the Vedas.

Little is known about the Vedic people who lived more than three thousand years ago in northern India: they left behind almost no objects, images, ruins. Only a 'Parthenon of words' remains: verses and formulations suggesting a daring understanding of life. 'If the Vedic people had been asked why they did not build cities,' writes Calasso, 'they could have replied: we did not seek power, but rapture.' This is the ardor of the Vedic world, a burning intensity that is always present, both in the mind and in the cosmos. With his signature erudition and profound sense of the past, Calasso explores the enigmatic web of ritual and myth that define the Vedas. Often at odds with modern thought, he shows how these texts illuminate the nature of consciousness more than neuroscientists have been able to offer us up to now.

http://www.bookdepository.com/Ardor-Rober-Calasso/9781846145070?ref=grid-view

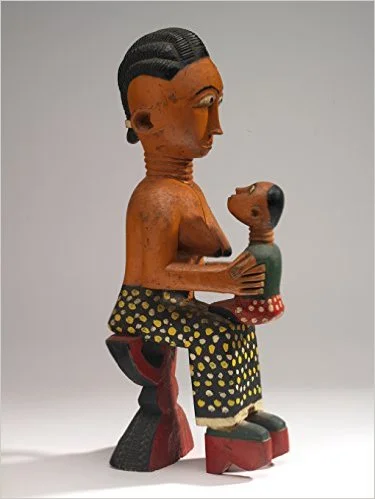

New book: Africa in the Market

Every now and then we will post about new books that we find on areas of interest to our clients. Here is one new release that caught our attention.

Africa in the Market, which is richly illustrated, introduces to the public the artwork in the Amrad African Art collection at the Royal Ontario Museum.

by Silvia Forni (Editor), Christopher Steiner (Editor)

Every now and then we will post about new books that we find on areas of interest to our clients. Here is one new release that caught our attention.

While many publications focus on the aesthetics and symbolism of African art, few explore the historical dynamics and exchanges that have informed the way people in Africa have created, preserved, collected, and sold their artworks to local and foreign patrons. The book addresses key issues of market trends, the transformation in taste and aesthetics in relation to changing historical conditions, and the role of artisans, traders, and collectors in mediating knowledge and value in the international art market.

Africa in the Market, which is richly illustrated, introduces to the public the artwork in the Amrad African Art collection at the Royal Ontario Museum. The collection contains a wide range of mostly 20th century pieces that illustrate the creative achievements and cultural meanings of art objects produced and/or collected at a time of great international expansion of the market for African art. The objects are framed and interpreted within academic essays that highlight the significant role that African makers and dealers have played in shaping Western understanding of African art. The essays are based on the long-term fieldwork of a number of anthropologists and art historians who have contributed original and innovative research to the discussion. The book explores the significance of 20th-century artistic production as a material component of local traditions and, at the same time, as artifacts circulating in a global market where local specificities are often lost.

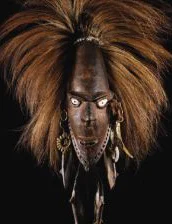

The Magic Flute Stopper and other tales from PNG

It is not often that an Oceanic artwork trumps the big African art names at Sotheby’s in Paris, but it did in 2012 when €1.4 million was paid for a Biwat flute stopper from PNG. I suspect that many of the African bidders at that sale had never heard of the Biwat – as opposed to the Fang, or the Kuba, or the Dogon – and maybe didn’t know what a flute stopper actually was, so let me explain.

by David Said

It is not often that an Oceanic artwork trumps the big African art names at Sotheby’s in Paris, but it did in 2012 when €1.4 million was paid for a Biwat flute stopper from PNG. I suspect that many of the African bidders at that sale had never heard of the Biwat – as opposed to the Fang, or the Kuba, or the Dogon – and maybe didn’t know what a flute stopper actually was, so let me explain.

New Guinea society and religion is quite different from other tribal cultures. The social structure is flat and democratic, and the population fragmented. There are more than 800 distinct languages and people tend to live in villages, then in clans within villages. There are almost no hereditary chiefs and status had to be earned in one’s own lifetime. In many groups, individual status is judged by how much wealth one gives away, not by how much one keeps.

New Guineans were traditionally animists and ancestor worshipers, and because their small social groups were surrounded by a hostile environment where a drought, fire or an enemy raid could wipe out your entire world, great emphasis is placed on controlling the spirits of ancestors and of nature to protect against these disasters. As a result, outside the skills of day-to-day technology, almost all knowledge was concentrated on how to control these spirits.

The majority of New Guinea art springs from this source – statues, masks and other artworks are primarily carved as temporary homes for the spirits, who are summoned or enticed to live in them while the ceremony or ritual takes place. In contrast to Africa, where secret society masks and symbols were stored and treasured, New Guinea art was quite often burned after the ceremony to destroy traces of the dangerous spirits that had lived in it, and to let their power drain back into the earth.

Along the Sepik, PNG’s river of art, one common way of proving that the spirits were indeed attending ceremonies was to provide them with a voice, and this was the function of the sacred flute, called wusear in the Biwat language. The flutes themselves were ridiculously simple – just a bamboo tube blocked or stopped at the bottom. They were played by blowing across the opening, like a bottle neck, to produce one note only, and always played in pairs to perform plaintive two note melodies. When the flute was playing, usually out of sight behind a screen, the initiated and the uninitiated alike believed that the spirits were present.

The bamboo pipes probably had a short life, but the stoppers were often kept and reused for many more ceremonies. The popular theory is that because they had the power to produce the voices of the spirits, the flutes had to be protected against evil spirits, hence the protective carving on the stoppers. In fact, John Friede, who once owned the world's largest private collection on of New Guinea Art, has a more convincing theory, which is that the bamboo tube was just that, a bamboo tube, but the real essence of the power of the spirit was incorporated into the elaborately carved stopper which actually represented the spirit voiced by the flute. Certainly, if one regards carvings as abodes for spirits, this makes perfect sense.

So much for the flute stoppers – now for the Biwat, who Margaret Mead confusingly named the Mundugumor. They live on the Yuat River which flows into the Sepik system. The Biwat/Mundugamor are famous for hoodwinking Margaret Mead by making up all sorts of fairy stories about themselves to entertain her. The Yuat river was also relatively accessible by canoe from the Government Control Post at Angoram on the Middle Sepik, and was therefore explored by anthropologists and collectors, converted by missionaries and cleared out of most old artefacts a long time ago. In fact, Margaret Mead stated that the flute ceremonies were abandoned by 1930, so there are very few wusear flute stoppers around. That’s one reason why they are so expensive.

Add to this scarcity their power and beauty, and it is easy to see why they attract high prices at any auction, even without the embellishment of the cassowary feathers and shell valuables. In fact, it seems quite likely that the figures were stored stripped bare of ornaments for storage and only dressed up for ceremonies. One excellent example, of which only the wooden figure survived, was sold by Sotheby’s in 2011 for almost €290,000. By contrast, the stopper sold in 2012 achieved 5 times that price, and it is interesting to ask why.

The record-breaking example was, of course, fully dressed with exception of the human hair beard, which seems to be missing in almost all collected examples and a missing nose decoration. It is undoubtedly a superb carving. The aggressive stance of the spirit figure, the staring shell eyes, the extravagant head dress of cassowary feathers and the lavish ear decorations of shell valuables clearly proclaim its importance and power, but it is its watertight provenance that stakes its claim to a record price. It almost certainly originated from the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin, then owned by two generations of the Speyer family before being acquired by the famous Dutch collector Louis Lemaire, and passed down to the vendor, his granddaughter.

When they secured this masterpiece, the new owners, be they an individual or a museum, purchased the equivalent of a Ruebens or a Goya of the world of Oceanic art at a fraction of the cost of a European masterwork. The rest of us will just have to keep scouring the auction sales while we search for that once in a lifetime piece of New Guinea art.

A version of this article first appeared in David Said’s blog, In Praise of Tribal Art. Copyright David Said, February 2016.

Collector's Notebook: Shabti Figures

It is beleived that Shabti figures developed from the servant figures common in tombs of the Middle Kingdom. They were shown mummified, like the deceased, with their own coffin and were inscribed with a spell to provide food for their master or mistress in the afterlife.

It is believed that Shabti figures developed from the servant figures common in tombs of the Middle Kingdom. They were shown mummified, like the deceased, with their own coffin and were inscribed with a spell to provide food for their master or mistress in the afterlife.

From the New Kingdom (circa 1550-1070 B.C.) onwards, it was believed the deceased would live for eternity in the ‘Field of Reeds’, and so they were expected to assist with its’ maintenance. Such work included agricultural labours, ploughing, sowing, and reaping the crops. Understandably, the deceased were keen not to personally undertake this work throughout eternity, so the Shabti figure was created as a servant that would carry out heavy work on their behalf. The mummiform figures held agricultural implements such as hoes. To ensure the deceased would not be called upon for manual labor, the Shabti’s were inscribed with a spell which ensured they answered when the deceased was called to work – hence the name ‘Shabti’ (meaning ‘answerer’).

From the end of the New Kingdom, anyone who could afford to do so might have a total of 401 figures – one for every day of the year, with an overseer figure for each group of ten labourers. Many individuals had several sets. These vast collections were often of extremely poor quality, uninscribed and made of mud rather than faïence, which had been often used in the New Kingdom.

AN EGYPTIAN PALE AZURE GLAZED FAÏENCE SHABTI, Late Period, Circa 600-300 B.C., 12.5cm

Collector's Notebook: The Indus Valley

Dating from c.6th millennium BC on the Northwest frontier of India, lies the Indus Valley, home to one of the three Old World civilisations, the other two of which were Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Dating from c.6th millennium BC on the Northwest frontier of India, lies the Indus Valley, home to one of the three Old World civilisations, the other two of which were Egypt and Mesopotamia. Covering an area of 800,000 square kilometres, and with up to 5 million inhabitants, it was the most widespread of these three civilisations and was located along two of the great rivers of Asia, the Indus and, the now dry, Sarasvati.

Archaeologists including MS Vats, in the 1920s and Mortimer Wheeler in the 1940s, have identified over 1000 towns, only about 100 of which have been excavated to date. Larger urban centres such as Harappa, located in what is now Punjab in Pakistan, contained grand public architecture and given the complexity of planning, there was clearly an administrative structure to the society that built structures such as dockyards, granaries, warehouses, and protective city walls. However, quite unlike in the other two Old World civilisations, the architecture of the region seems to have been far more functional, as they appear not to have built large monumental structures – such as the pyramids.

As well as the urban structures, other aspects of the Indus civilisation would have been extremely familiar to us in the 21st century, particularly that they were one of the first civilisations to develop a uniform system of weights and measures, with weight based on a metric system.

One of the more familiar artefacts found in the region is the fine-grained earthenware pottery. This was ochre-coloured and often highly decorated, usually with black outlines, then sometimes with an in-fill of red, yellow, white, and blue pigment. The patterns were often geometric and depicted a variety of animals including fish, birds, cows, goats, antelopes, and lions.

As well as pots, clay idols and animal figures are also characteristic, some of which are solid, others have hollow bodies to avoid them bursting during firing. Much like the depictions on the pots, animal figures included bulls, pumas, birds, rams, goats, and fish.

And what does their script tell us about them and their world? At present this remains a mystery. We have no Rosetta Stone for the Indus people and their language, however, some small steps forward are being made and with only 10 percent of the area excavated, it may not be too far off before we hear from these ancient people more directly.

Guy Earl-Smith Art & Antiquities

Australia’s only boutique antiquities and tribal art auction house.

Since 2000 A.D.

We run several auctions annually. To consign works of art for an auction please contact us on the addresses below.

Contacts

Guy Earl-Smith

Northern Qi Dynasty, China 550-577 AD

As the Roman Empire continued its long decline in the west; in the East, the rise of a new Chinese Dynasty was taking place: The Northern Qi.

As the Roman Empire continued its long decline in the west; in the East, the rise of a new Chinese Dynasty was taking place: The Northern Qi.

Following the collapse of the Han Dynasty in the early third century, China suffered almost 300 years of war and political turmoil.

Commonly known as the Period of Disunion, it was characterised by violent power struggles between a succession of small kingdoms and repeated invasions from beyond the Great Wall. People were also arriving from the exotic lands of the east such as Persia and India and this influenced a transformation of Chinese art and culture in the north.

We may now look back at the Northern Qi Dynasty that followed this turmoil as a time of cultural convergence and cosmopolitanism, which included one of the most significant transformations of the time – the adoption of Buddhism from the east.

This convergence of Chinese culture with foreign influences produced a distinctly different style of art to that of southern China where Confucian values and the traditional 'Chinese' identity in political, cultural and religious life were being preserved.

Although the Northern Qi Dynasty only lasted about 100 years, it would have a significant impact on Chinese art for centuries to come. Buddhism brought a profound peaceful influence and with it began a distinctive minimalist style of art in line with Buddhist principles that would eventually spread throughout China.

Along with this distinctive style of art came innovative ceramic production techniques that would continue to be refined for centuries to come. Importantly due to these and other remarkable achievements, the Northern Qi Dynasty may well be considered the precursor to what is arguably the beginning of the Chinese Renaissance of art during the Tang Dynasty.

Cave Temples

Most impressive in scale were the incredible Buddhist cave temples and the sculptures held within them, of which the limestone statue pictured above is an example.

Most Northern Chinese cave temples were established by Imperial decree. Originating in Central Asia, these vast monuments were hollowed out from rock outcrops and decorated lavishly within. It was considered that the very act of creating these monuments was an act of piety resulting in the accrual of merit and spiritual liberation.

The 6th Century cave complex at Xiangtangshan, established by Imperial decree, exemplifies the importance of Buddhism in the life and culture during the time of the Northern Qi dynasty.

A Northern Qi Dynasty Gilded Limestone Sculpture Of Buddha, c.550-577 AD 153 x 40cm, sold AU$29,000 (image)

The Northern Qi statue (top), is an example of the quality of material culture that is consigned with us. Originally from the collection of a Hong Kong resident, this work was purchased by an astute Australian collector at one of our past auctions.

Of museum importance and quality the sculpture exhibits superb detail and craftsmanship. Standing above a separate lotus base wearing a diaphanous robe, his left hand raised in vitarka mudra and his right hand in bhumisparsa mudra, the fine-featured visage with serene expression flanked by pendulous ears below a wavy coiffure and top knot at apex, gilded and decorated with polychrome mineral earth pigments.

A similar work was sold by Sotheby’s New York, Fine Chinese ceramics and works of art, March 31 and April 1, 2005, lot 86.

See also:

- The Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, Australia, exhibition 2008, ‘The Lost Buddhas’

- Xiaoneng Yang (ed) 1999, The Golden Age of Chinese Archaeology; Celebrated Discoveries From The People’s Republic of China, National Gallery of Art Washington, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Yale University Press New Haven and London